On February 7, the Spelman College Museum of Fine Art will open its spring exhibition, "Amanda Williams: We Say What Black This Is," featuring works by MacArthur award-winning artist Amanda Williams. At the heart of the exhibition is a celebration of the resiliency and depth of Blackness brought to life through the voices of Atlanta University Center students.

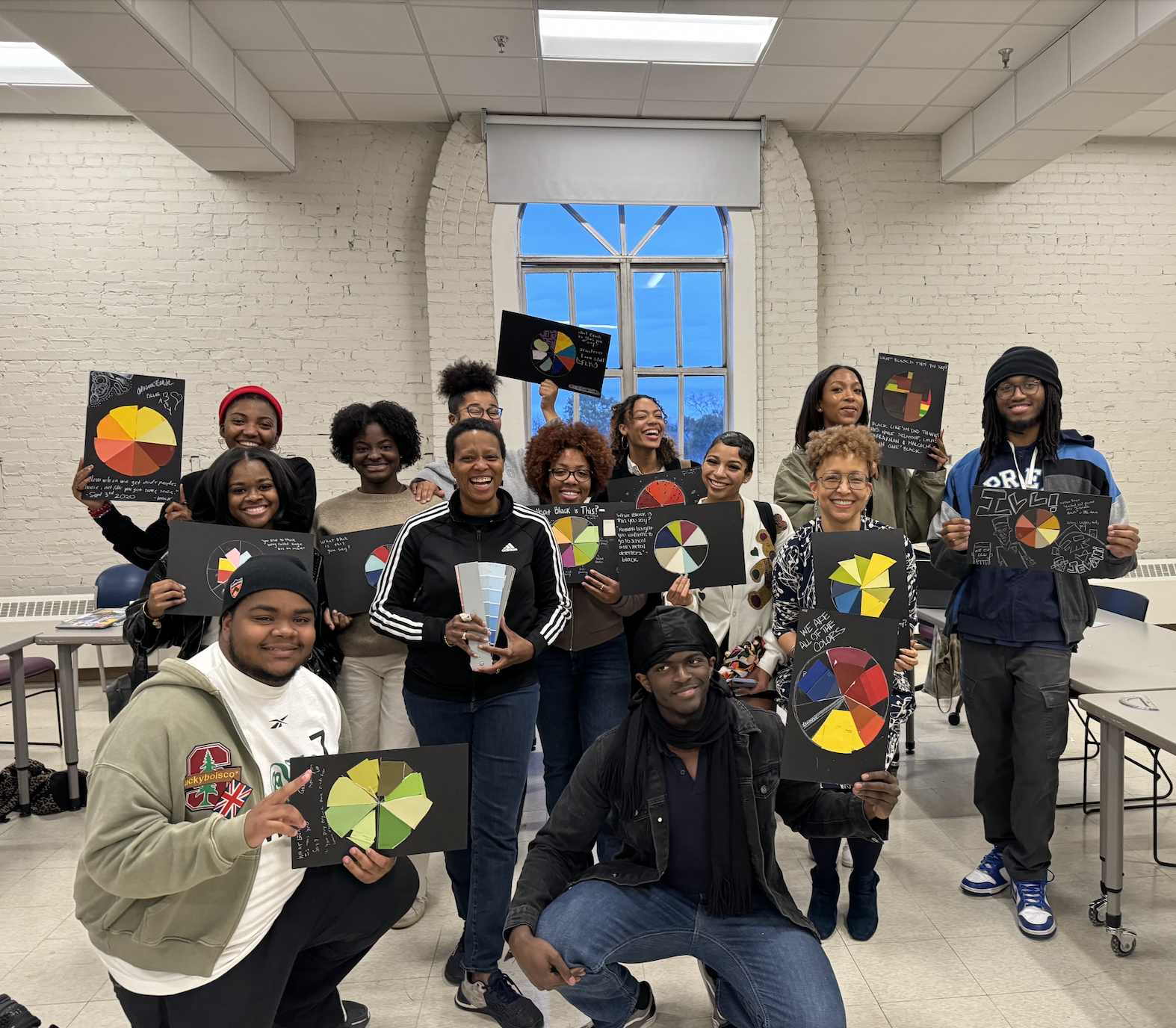

Last spring, 13 AUC students took The Special Topics: Amanda Williams class through the AUC Art Collective. The course, taught by Dr. Cheryl Finley, inaugural director of the Atlanta University Center Art History & Curatorial Studies Collective, and Karen Comer Lowe, curator in residence at the Spelman Museum, allowed students to develop thematic frameworks, engage with the artist’s studio practice and write didactic labels for the artwork – some of which will be featured in the exhibition. The students had the opportunity to travel to Williams’s studio in Chicago to engage with her in person.

Last spring, 13 AUC students took The Special Topics: Amanda Williams class through the AUC Art Collective. The course, taught by Dr. Cheryl Finley, inaugural director of the Atlanta University Center Art History & Curatorial Studies Collective, and Karen Comer Lowe, curator in residence at the Spelman Museum, allowed students to develop thematic frameworks, engage with the artist’s studio practice and write didactic labels for the artwork – some of which will be featured in the exhibition. The students had the opportunity to travel to Williams’s studio in Chicago to engage with her in person.

Each artwork title in the exhibition reflects an authentic aspect of Black culture that showcases the diversity of Black identity. The students were given the unique opportunity to select one of Williams’s works and write meaningful descriptions using only the paintings and their titles as a guide.

Spelman student Chloë Catrow, C’2025, art history major and curatorial studies minor, chose to describe a work titled "What black is this you say?—'You refuse to stop saying ‘irregardless’ despite knowing that it is in fact NOT a word.'—black" (06.12.20), 2020, oil, mixed media on wood panel, 20 x 20 inches.

“I understand these ‘riddles’ and the conversations she’s having through these titles, because I am Black and have grown up around Black people my entire life,” said Catrow. According to her description, this stubbornness and refusal to conform to Western practices highlights the cultural use of double negatives used frequently throughout the African American English dialect.

For art history major Robyn Simpson, C’2025, engaging with the exhibit and traveling to the artist’s Chicago studio changed the way she sees Blackness expressed through art.

“I think Amanda Williams is a one-of-a-kind artist. The color palette she uses in her work to relate facets of the Black experience into visual expressions of Blackness was something that opened my mind to the way Blackness can be physically represented,” said Simpson. “She’s so innovative in the way that she captured all of the different ways that Black people view the world, including Hispanic heritage within the diaspora.”

“I think Amanda Williams is a one-of-a-kind artist. The color palette she uses in her work to relate facets of the Black experience into visual expressions of Blackness was something that opened my mind to the way Blackness can be physically represented,” said Simpson. “She’s so innovative in the way that she captured all of the different ways that Black people view the world, including Hispanic heritage within the diaspora.”

Simpson chose to describe a work titled, Amanda Williams, "What black is this you say?—'You wish you could see the black on the inside of Stevie Wonder’s eyelids so you too could have inner visions'—black" (09.24.20), 2021. In her didactic label, she describes the way Stevie Wonder’s 1973 album "Innervisions" resonates with the Black community, providing herself as an example: “'Don’t You Worry Bout a Thing,' in particular, has provided me solace in times when grief and disillusionment weigh on me during unprecedented attacks on Blackness in the U.S.,” Simpson wrote in her description.

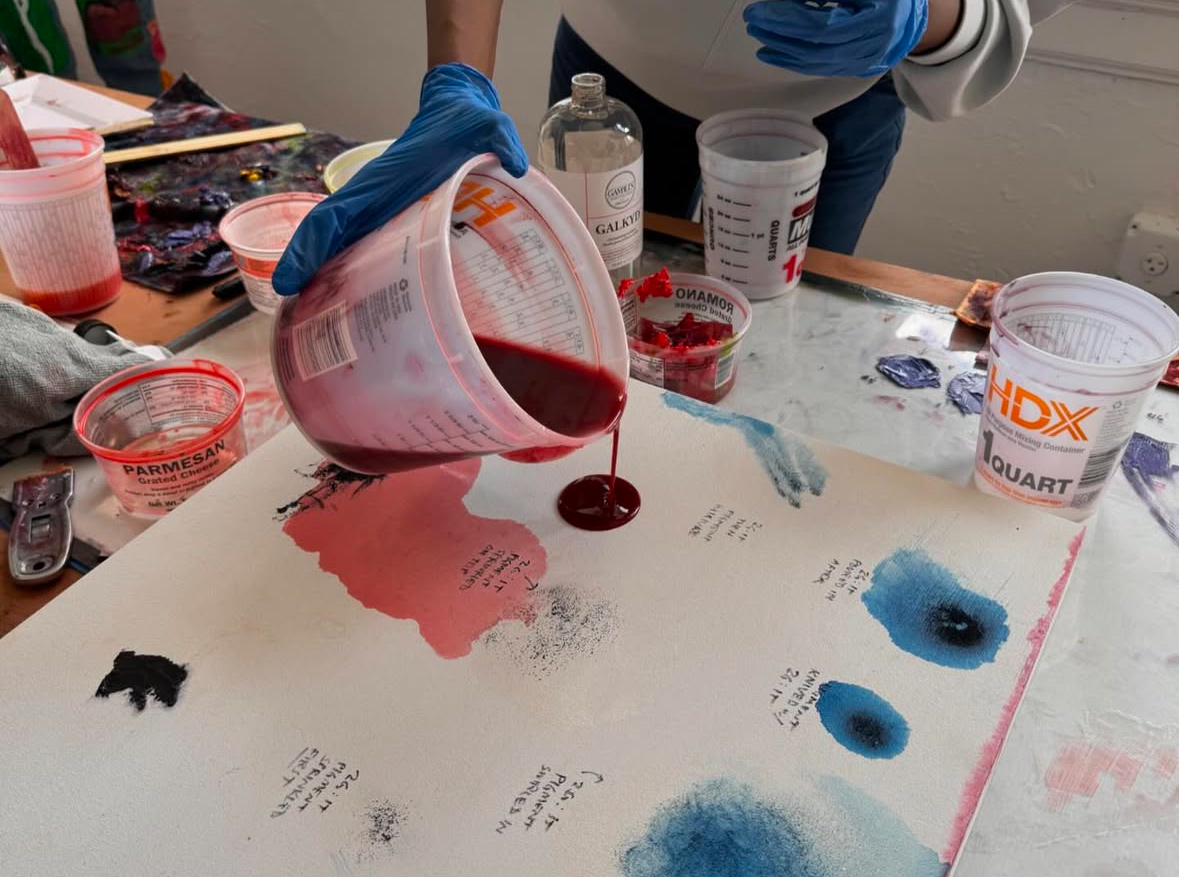

Throughout the class, the students had two virtual meetings with Williams to gain a better understanding of her art practice and receive detailed feedback on their written descriptions. At the artist’s studio in Chicago, the students learned how Williams comes up with colors and concepts.

Kayla Golden, C’2025, art history major with a double minor in curatorial studies and writing, aspires to one day become a head curator. For Golden, working with Williams helped her master skills in didactic label writing – a skill she used heavily as the fashion arts curatorial research intern for the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston last summer.

“The studio visit was important to me. Originally, I was worried about interpreting her art correctly; how she views it. In the studio visit, she told us ‘Do whatever you guys feel comfortable with. Whatever speaks to you from that piece is what I want to see,’” said Golden. “So, I think that helped a lot of us understand that she really just wanted us to be creative in our own way.”

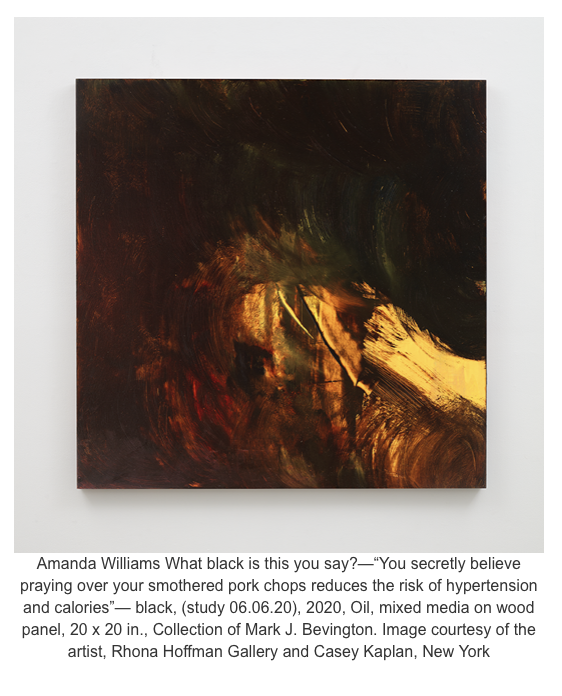

Golden’s favorite description she wrote was for a piece titled, Amanda Williams, "What black is this you say?—'You secretly believe praying over your smothered pork chops reduces the risk of hypertension and calories'—black" (study 06.06.20), 2020. She said the piece resonated with her because of her own experiences with medical conditions within her family – an example of the authenticity reflected throughout the exhibit.

Golden’s descriptions will be featured alongside their respective titles in the spring exhibit that opens on February 7 and runs until May 24, 2025. The full descriptions written by Catrow, Simpson and Golden are included below.

For more information about the exhibit, visit spelman.edu.

Chloë Catrow

Chloë Catrow

Spelman College, Class of 2025

Amanda Williams, "What black is this you say?—'It’s easier for young black men to rip an entire ATM out of a bank drive-thru machine and crack it open to get to the money than it is for them to get a job, Bank Account or Loan from that same bank'—black" (06.03.20), 2020

Quick, short, and sporadic are the movements of yellow and green colors across a dark red, blue, and purple background. This group of adjectives could describe the movements of someone trying to steal an ATM machine from a bank. But they could also describe the rejection of Black men seeking assistance at a bank: quick, short, and sporadic. It is the denial of financial help (which one needs in order to survive in this capitalistic society) based on a person’s skin color. This issue, however, is rooted in an unfortunate history. Though slavery in America was “abolished” in 1865, Jim Crow laws were formed to continue the disenfranchisement of formerly enslaved people in America. They denied Black people access to housing, education, and jobs. Additionally, Black people were unsafe and unsupported in the political sphere. Loopholes in the Fifteenth Amendment prohibited them from voting for laws that could increase Black economic stability. In the early to mid-twentieth century, Black workers were less likely to be included in federal labor financial support laws and Black neighborhoods suffered from redlining. Together, these lowered opportunities for Black people to increase wealth and created economic issues that persist to this day. What can a young Black man do if he cannot receive financial help from the bank? How will the bank be held accountable for upholding discriminatory practices? How has racial discrimination ruined people’s lives? How will you hold yourself accountable for the discriminatory practices you display?

Robyn Simpson

Robyn Simpson

Spelman College, 2025

Amanda Williams, "What black is this you say?—'You wish you could see the black on the inside of Stevie Wonder’s eyelids so you too could have inner visions'—black" (09.24.20), 2021

Innervisions was released by revered singer/songwriter Stevie Wonder in 1973 as his 16th studio album. Praised by critics, Wonder’s album is widely considered one of his best and most iconic works. Carefully crafted, the album examines an array of issues, from the harrowing effects of drugs to the harsh and unjust realities of city life, resonating with millions of Black Americans of the time. This abstraction captures the striking brilliance of Wonder’s artistic and musical vision. Black and scarlet layers of paint mimic the shapes seen on the inside of closed eyelids, imagining the visual world of Stevie Wonder that influenced the iconic album, which has captured Black people's hearts for generations. Don’t You Worry Bout a Thing, in particular, has provided me solace in times when grief and disillusionment weigh on me during unprecedented attacks on Blackness in the U.S. Wonder seamlessly blends several genres, balancing darker subjects with themes of hope and joy, a contrast that Williams captures through her use of contrasting light and dark colors. This work serves as a reminder that Blackness moves beyond what is physically tangible, reflecting on what is heard and felt when you allow yourself to close your eyes and have your own Innervisions. What lies inside? What begins to take shape? In a world that judges Black folks solely based on visual presentation, solely based on color, Williams invites us to discover a world within ourselves beyond what we can see with our own eyes."

Kayla Golden

Kayla Golden

Spelman College, Class 2025

Amanda Williams, "What black is this you say?—'You secretly believe praying over your smothered pork chops reduces the risk of hypertension and calories'—black" (study 06.06.20), 2020

What black is this you say?—“You secretly believe praying over your smothered pork chops reduces the risk of hypertension and calories”—black” helps to create a conversation between the African American community and our relationship with food and medical conditions that are caused by poor eating habits. In the Black family, health is always a topic of conversation, especially when it comes to holidays leading to family gatherings and reunions. Everyone knows and can think of at least one person in their family who has dietary restrictions due to some type of medical condition. Some common health issues that disproportionately affect Black people include diabetes, cancer, and kidney failure. During these family gatherings, they are constantly monitored by a close relative to make sure they aren’t going against their dietary plan despite the special occasion. This piece helps to bring awareness that the typical food we eat, like grandma’s good ole southern cookin’, continues to raise the number of African Americans who are predisposed to certain medical conditions. Williams’s use of orange and red, which she associates with “Flamin’ Red Hots” and “Harold’s Chicken Shack” in her 20014-16 series Color(ed) Theory, by having these two colors cascading across the canvas and breaking through the black background helps reaffirm the idea that what we eat can and will flow through our body and leave a mark on our health.